Colourism on the Couch

Dr Yvon Guest

Welcome to Colourism on the Couch

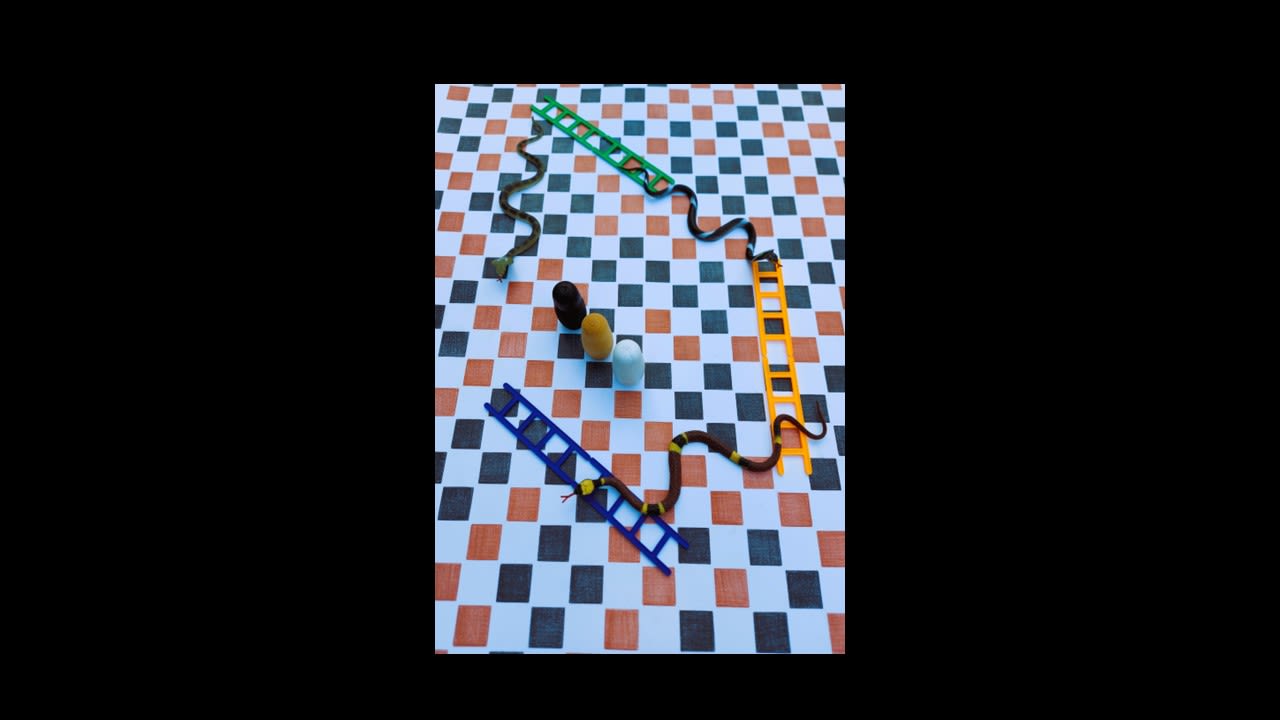

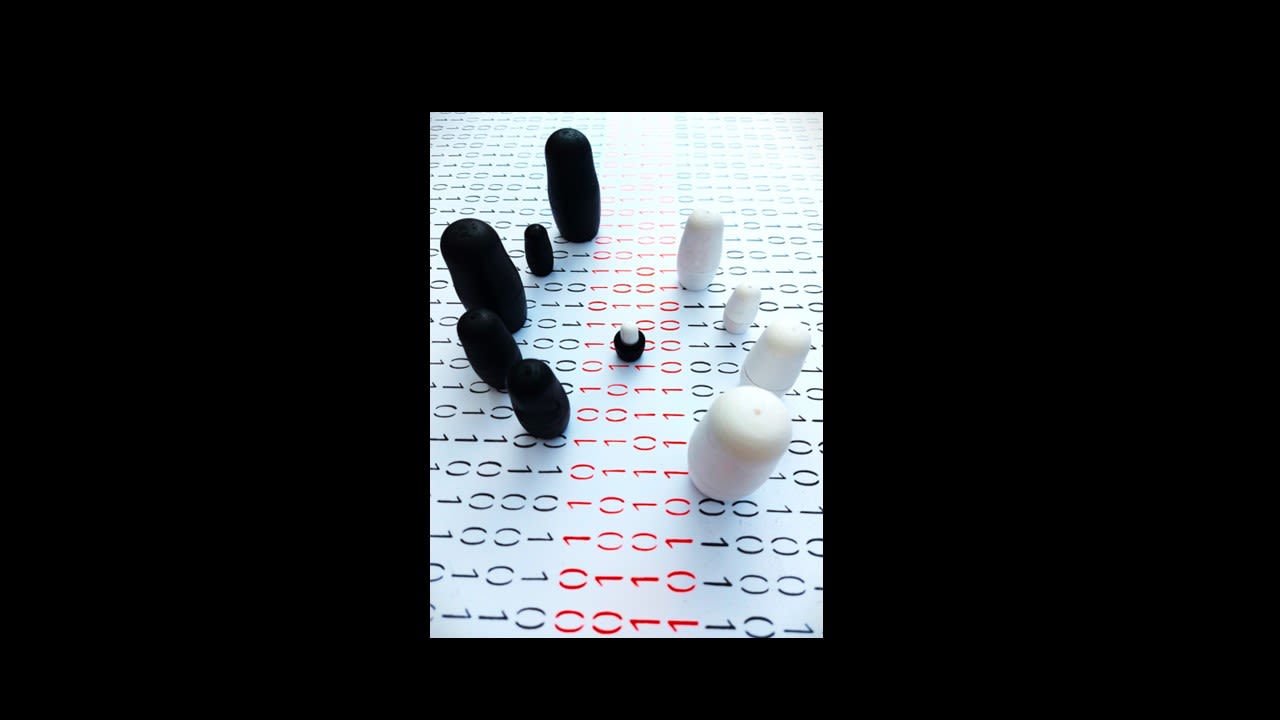

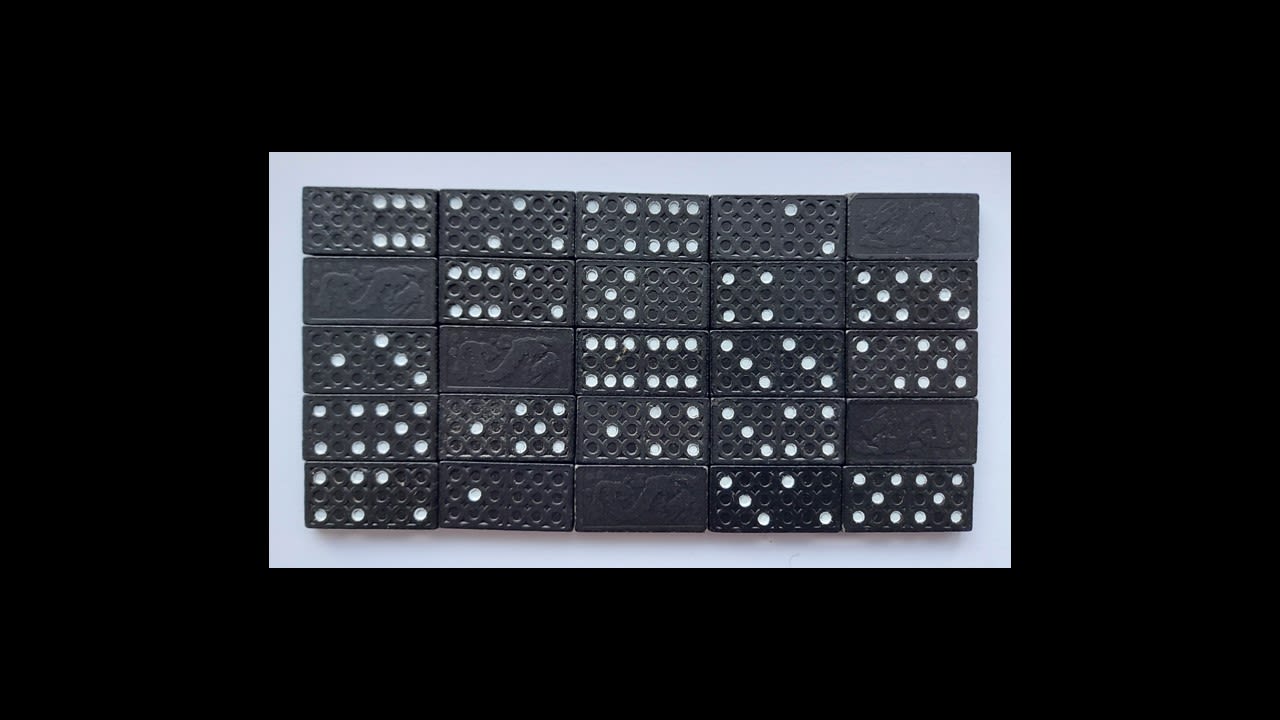

Thanks for taking the time to look at my photo essay. When I was first asked to create this project by Tony T and Rebecca Goldstone @sweetpatootee; I felt very strongly that I wanted to use my artwork with writing to explore how colourism shows up in my counselling practice. Thank you both for taking a chance on me - a totally novice artist. The use of toy figures and games represents childhood when colourism is often first experienced.

For those who are new to this topic, colourism is discrimination against individuals based on the shade of their skin. It is thought that those with the darkest skin experience more than lighter skinned people.

I am a mixed race counsellor of Jamaican, English and Irish heritage. I work with clients from communities that were part of the British Empire, mostly South Asian or African ancestry. First, second or third generation, generally born or raised here in the UK.

None of this, or anything I do, is possible without the love and support of my family, Mike Smith, Seb Grzimek, Roz Grzimek, and my muses Amirah Grzimek and Inayah Grzimek. Friends; Kimberley Fuller, Julia Bellabarbara, Sylwia Korsak, Lizzie Goodchild, and supervisors Paul Hoggett and Charles Brown.

In loving memory of Felix Fehrer: 22 June 1977-18 July 2022.

400 years : Yvon Guest 2022

400 years : Yvon Guest 2022

400 years

In my work as a counsellor, I always use a life history approach, to understand what has shaped people. Clients will usually include their parents and grandparents, but we never go further. I would like to go back 400 years to remember what happened between white and Black, and Brown people in the context of the British Empire.

Just to explain my use of language here and going forward, when I use terms such as Black, Brown, mixed race/dual heritage. These concepts are socially constructed, they didn't exist until they were invented by people.

'Across three-and-a-half centuries, whiteness has been wielded as a weapon on a global scale; Blackness, by contrast, has often been used as a shield' (Baird 2021).

The grouping of people into category by skin colour and continent: White, Black, Yellow, or Tawny, and Red first appeared in the 18th century (Linnaeus, 1758). Whiteness was used to justify the harsher treatment of slaves of African descent.

Black was embraced by Black people in the USA towards the end of the 1960's to replace Negro. In the 1980's African American began to replace Black as an ethnic identity was seen as more appropriate than a racial one. Southern Europeans and Southeast Asians were originally included as Brown. Currently, some South Asians, South Americans, Black and mixed race people also identify as Brown. The reality is that many shades of skin types have existed simultaneously on different continents before European colonisation.

Historically, terms that originated in slavery, such as half caste or mulatto, have been used to describe mixed race people. Currently, some say dual heritage or biracial. Whether we use the concept of race, culture, or heritage it always comes down to white being seen as superior (Olyedemi, 2013). So not only is the language around race socially constructed it is continually evolving.

By the 18th century, slavery which had existed for thousands of years was conducted by the British and other Europeans on an industrial scale during the transatlantic slavery period. As the slaves were loaded into the holds of the ships, in the story of humankind, this was truly a descent into darkness.

Following emancipation from slavery, empirical subjugation and segregation, the fight for basic civil rights has been a fight to be recognised as human. Black and Brown communities are fighting back and gaining ground. But for many around the world and here in the UK there is still enormous racial, social, and economic inequality.

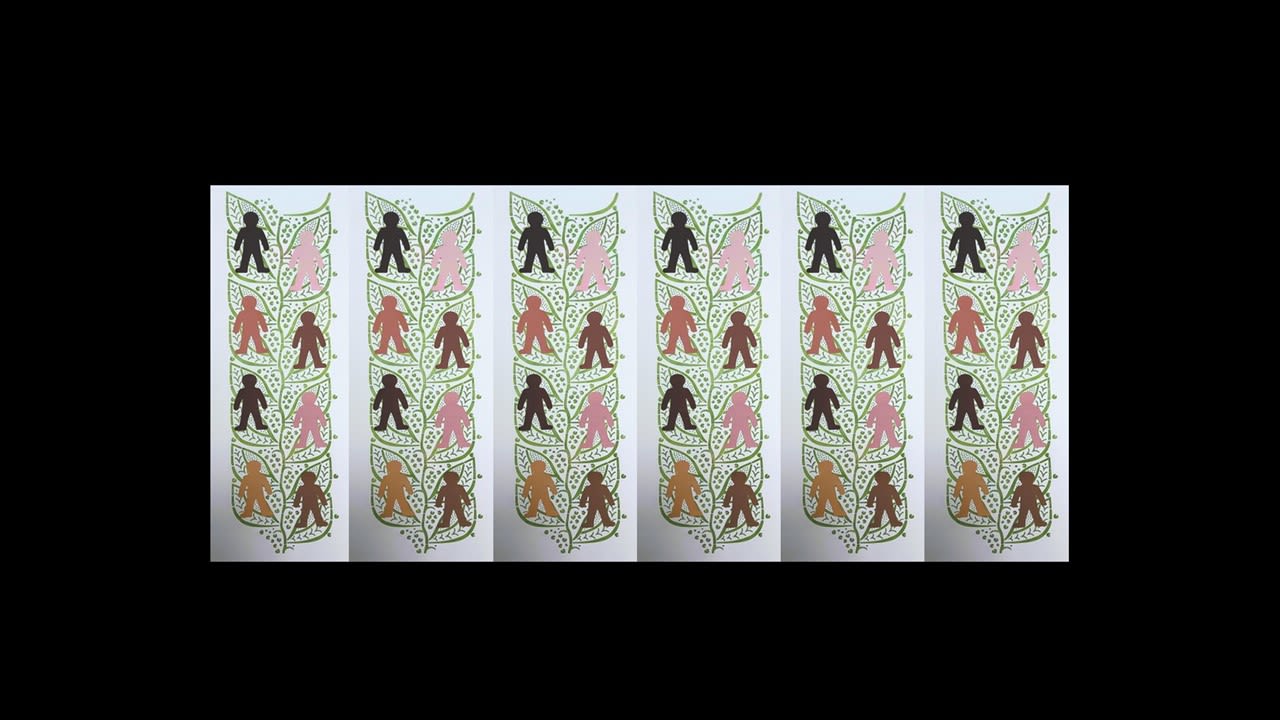

Miscegenation: Yvon Guest 2022

Miscegenation: Yvon Guest 2022

Racial mixing

Before white people journeyed to the colonies, they were predisposed to a prejudice that anything black or dark was bad or negative. On arrival, they projected all that was savage and animal into Black and Brown people and maintained an idealised picture of themselves as ‘civilized. Fanon (1967) held that encountering white colonialists left Black people with a ‘colonised mind’; the belief that to be white was to be good and to be Black was to be bad and inferior.

Colourism also has roots in the transatlantic slave trade. When white males forced female slaves into sexual relations, they created classifications based on how light or dark the skin shade of the offspring was. This established a skin shade hierarchy amongst slaves. Being lighter skinned positioned household slaves closer to the master, with a greater chance of education and freedom. Darker skinned slaves were further away, undertaking more physically demanding field work, subjected to brutal treatment.

In India variations in skin shade existed before the British arrived, however the caste system was not based primarily on skin shade. The British gave preferential treatment to those with the lightest skin. But to understand colourism in this context requires exploring a combination of factors; caste, class, religion, region, gender, and economics (Mishra, 2015).

From studies of Eugenics, geneticists argued that racial hatred is a natural mechanism of biology ensuring racial segregation (Popenoe & Johnson, 1918). Other races would gain from miscegenation (racial mixing), because of the superiority of the white race (Provine, 1973). Legislation ensured that the races did not mix on the slave plantations and throughout the colonies. But individuals did form interracial partnerships and created mixed offspring.

Following the abolition of slavery 1834 there was no legislation against racial mixing in the British Empire. In some places, such as New Zealand, the Maori population was encouraged to mix with white settlers with the hope that they would cease to exist. This failed because the Maori identified mixed race offspring as full Maori as did the offspring themselves (Salesa, 2011).

Some believe the settlers invited by the post war British government, from the former colonies, brought skin tone hierarchies with them (Gabriel, 2007). Racist and ethnic discrimination in the white population at that time grouped all non whites and some whites together. Hence the signs in pub and landlords’ windows 'No Irish, no Blacks, no dogs'. Others hold that whiteness as the global standard of beauty has contributed to colourism more recently (Pheonix & Craddock 2022).

Research is now expanding in the UK but has failed to draw out nuances and complexities around hair texture, or facial features. Research generally focuses on women's experiences and has not addressed colourism in the family. We know it does affect dark and light skinned people, men, and women. Colourism can happen between members of different racial groups and members of the same racial group; therefore, it divides communities (Craddock et al.2022; Campion, 2019; Gabriel, 2007). I feel it is best to see colourism as a perfect storm - there are many factors involved.

Expectations: Yvon Guest 2022

Expectations: Yvon Guest 2022

When a child is born

For most of the clients I see, their first experiences of colourism happened in the family. This was further complicated by inconsistencies. I am protecting identities of clients by changing names, other details, and creating vignettes.

Jen is a dark skinned woman from the Caribbean. Her mother favoured. her much lighter skinned siblings. When she felt ready to be a parent, Jen chose a darker skinned partner. She and her girlfriend are raising their dark skinned daughter to be proud of her appearance.

Shula, also from the Caribbean, was dating an Ethiopian. Her parents opposed marriage; they feared their grandchildren would be very dark. Shula previously dated mixed race men. But her grandmother doesn’t approve of mixed race people because they have white relatives. She doesn’t want anyone bringing white people into her family, as her family have suffered so much because of white people since coming here.

Yanni, Nigerian was raised here. He is the eldest son, there is no question of him marrying outside of his community. He carries a lot of financial responsibility for his family and the wider family. He feels a lot of resentment that his grandfather paid for his mixed race cousin's private education whilst he went to a state school.

Anisha is of mixed race Indian and English heritage. When her parents met, her white grandparents gave them permission to marry. But told them they should never have children because the world is such a cruel place. When she was born light skinned, her English grandparents were relieved. They love her but never acknowledge her mixed heritage. Her Indian grandparents refused to give permission for the marriage and barely acknowledge Anisha. When her mother's sister, married an Indian and had darker skinned girls the grandparents were upset, as it would make finding the right husbands much harder.

The family plays an important role in protecting a child from racism in the outside world. If a child is being subjected to colourism in the family that layer of protection layer is compromised.

Re positioning: Yvon Guest 2022

Re positioning: Yvon Guest 2022

Re positioning

Marie is of Ghanaian heritage, raised by white adoptive parents in a small town. She remembers being terrified as a child, surrounded by gangs of white children laughing at her, calling her the N word, saying she had been left in the oven too long. Her privacy was constantly invaded by curious strangers pointing out that she was clearly not her adoptive parent's child.

She felt like the ugly duckling with only white girls to compare herself to; that she must be an alien because she didn't understand her origins. Her adoptive parents would say - white people sit on the beach for hours to get brown like you. In the wider family, overtly racist comments were constantly made about too many foreigners in the UK. She was made to feel she should be grateful for her place in this white family.

She chose a city with a Black population for university, to finally be in a space where people looked like her. She was deeply disappointed and traumatised when some Black people said she wasn't the same because she knew nothing about Black culture. They told her you can't call yourself Black if you haven't had the lived experience of the Black community. Some of them called her a coconut.

Cerri of Barbadian heritage grew up like Marie. She had similar experiences at university. Dating Black men was hard, she was too white culturally for some, too dark skinned for others. At the same time, she was dealing with racism from white students. Now a professional; white and lighter skinned people talk over her in meetings, don't make eye contact or address questions to anyone except her. Having spent her childhood feeling highly visible, she now feels invisible. Karis Campion addresses the issue of how Black identity is policed. According to her we have been working with:

'… essentialist and ultimately fragmented conceptualisations of Black identity. In light of this, it shows the need for a conceptualization of Blackness that recognizes the ever-growing diversity of the Black experience, to maintain the strength of Black political struggles and empower the Black community long into the future (Campion, 2019).

No Man's Land: Yvon Guest 2022

No Man's Land: Yvon Guest 2022

No Man's Land: navigating a black and white world

Mixed race clients talk about the difficulty being brought up in a white, Black, or Brown community. Some are raised in more than one community. Nula is Pakistani and Caribbean. With every social encounter, she is desperately trying to work out what the person in front of her wants her to be. She suffers from social anxiety, often she finds it easier to just stay at home on her own.

Some recall their parents apologising for their children being too dark or too light skinned. Cat has a Zimbabwean mother and English father. Her mum seemed ashamed, when strangers commented on how white her children were, or asked if they were hers. Cat is white presenting; proud of her African heritage but never allowed to claim that identity. She used to feel invisible. Some or her ancestors were Muslim, and she reverted, she finds great peace of mind in finally having a viable identity.

They have been coerced into taking on the identity of the community they were raised in order to gain acceptance. And forsaking the other half of their identity without understanding the importance. Colin, Indian and English, was raised in the white community. Both parents thought it was best for him to concentrate on one identity to avoid any confusion.

Sherri, Grenadian and English, was raised in the Black community. She was told she was Black, then constantly reminded that she was half white, but never allowed to talk about how that whiteness felt. For these clients, the burden of white ancestral, shame sits heavily on the one shoulder; whilst inter generational wounds from slavery and colonialism sit on the other.

White people were the perpetrators of past atrocities; in their psyche sits the knowledge we did that to them. Black and Brown people were their victims, in their psyche sits the knowledge they did that to us. Mixed race people hold both positions simultaneously, in their psyche sits the knowledge we did that to us.

If they reject binary identities, they find themselves in ‘no man’s land’ between two worlds. Tim, Nigerian and Scottish, was told to - go back to where you belong, many times in Scotland. He used to identify as Black. He went to Nigeria, to be with his people, and was deeply shocked to be called white. He now identifies as mixed race.

Cultural humility: Yvon Guest 2022

Cultural humility: Yvon Guest 2022

Cultural humility

From these vignettes and the literature, we know colourism happens in clients’ families, their communities, and in wider society. Some of the clients I see have never talked about it with anyone, often there is a lot of shame, anger, and humiliation. It adds another layer of trauma to the trauma of racism. The issue of what constitutes authentic racial, ethnic, or cultural identity, has the potential to undermine the collective struggle for freedom from centuries of white oppression.

Many times, I have heard Jamaican elders talk about their first encounters in British pubs playing dominoes. For them this was a lively game, and the pieces were banged down hard on the table. This did not go down at all well with the white pub goers, it was not culturally acceptable. The white people couldn't understand the cultural significance of playing dominoes like that: they lacked cultural humility.

Cultural humility is something therapists use, the ‘ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to the other) in relation to aspects of cultural identity that are most important to the client’ (Hook et al., 2016). Cultural humility requires constant reflexivity - reflecting and then adjusting one's thinking or behaviour. This could be a useful resource outside the therapeutic setting, not just between racial groups, as with the example of the dominoes, but also within racial groups in the context of colourism.

Thanks again for looking at Colourism on the Couch. I hope you feel it has increased your understanding of this issue. If you feel in any way negatively affected, I have compiled a list below of organisations where you can access help to process your reactions. If you want to explore this topic further there is a list references and resources to suit all learning styles.

Support

If you feel upset or troubled in any way after looking at this photo essay here is a list of organisations where you can find support.

If you are in need of urgent

support, these services are free:

Mind: www.mind.org.uk/need-urgent-help

The Samaritans:116 123

www.samaritans.org/how-we-can-help/contact-samaritan/talk-us-phone

Saneline: 0300 304 7000. Open 4.30pm – 10.30pm every day.

Shout: offers free confidential 24/7 crisis text support for times when you need immediate assistance. Text "SHOUT" to 85258.

Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM): Helpline for men. 0800 58 58 58. 5pm–midnight, 365 days a year.

Domestic abuse: 24-hour National Domestic Violence Freephone Helpline 0808 2000 247

Papyrus: Offers emotional support to people under 35 who feel that life is not worth living any more. Papyrus's HopelineUK 0800 068 41 41 is available from 9am to 10pm weekdays and 2pm to 10pm on weekends. Text 07786 209697.

If you feel you might need short or long term therapy (you will have to pay)

https://www.baatn.org.uk/find-a-therapist/ (Black, African, Asian, & therapists)

http://www.pinktherapy.com/en-gb/findatherapist.aspx (LGBTQIA+)

https://www.psychotherapy.org.uk/find-a-therapist/

https://www.bacp.co.uk/search/Therapists

https://www.counselling-directory.org.uk/

https://welldoing.org/find-a-therapist

References

Baird, R.P. (2021). ‘The invention of whiteness: The long history of a dangerous idea’, The Guardian, 20 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/apr/20/the-invention-of-whiteness-long-history-dangerous-idea?utm_source=pocket_mylist

Campion, K. (2019). You think you’re Black: Exploring Black mixed-race experiences of Black rejection. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 4(1), 196-213.

Craddock, N., Phoenix, A., White, P., Gentili, C., Diedrichs, P.C., & Barlow, F. (2022). Understanding colourism in the UK: Development and assessment of the everyday colourism scale. Ethnic and Racial Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2022.2149275

Fanon, F. (1967). Black Skin White Masks. Grove Press.

Gabriel, D. (2007). Layers of Blackness: Colourism in the African Diaspora. Bournemouth. ac.uk eprints. Available at: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/21409/

Guest, Y. (2019). Between black and white. Therapy Today,29(3) 26-29.

Guest, Y. (2022). Negotiating the Faustian pact: A psycho-social approach to working with mixed-race people. in Charura, D., & Lago, C.(eds) Black Identities + White Therapies: Race, Respect + Diversity (152-160) PCCS Books.

Hook, J., Farrell, J., Davis, D., Deblaere, C.,Van Tongeren, D., & Utsey, S.(2016). Cultural humility and racial microaggressions in counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology,63, 269-277.

Ifekwunigwe, J. (1999). Scattered Belongings: Cultural Paradoxes of `Race', Nation and Gender. Routledge.

Linnaeus, C., (1758). Systema naturae (Vol. 1, No. part 1, p. 532). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii): Stockholm.

Martin, B. L. (1991). From Negro to Black to African American: The Power of Names and Naming. Political Science Quarterly, 106(1), 83–107.

Mishra, N. (2015). India and Colorism: The Finer Nuances. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 14 (4). 725-750.

Olyedemi, M. (2013). Towards a Psychology of Mixed Race Identity Development in the United Kingdom. PhD. Thesis. Brunel University.

Phoenix, A., & Craddock, N. (2022). Black Men’s Experiences of Colourism in the UK. Sociology, 56(5), 1015–1031.

Popenoe, P., & Johnson, R. H. (1918). Applied Eugenics. New York: Macmillan.

Provine, W. B. (1973). Genetics and the biology of race crossing. Science, 182,790-796.

Salesa, D.I. (2013). Racial Crossings: Race, Intermarriage, and the Victorian British Empire. Oxford University Press.

Resources for further study

The following programs have been very helpful to me. I hope you find them useful:

The story of Africa https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/brand/p03njn4f

Bad blood the story of Eugenics https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001fd36

I am Black my partner is white stop asking me if this is my baby https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/stories-57897237

Stephen Graham Desert Island Discs (growing up mixed race) https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000bdlj

The death of nuance: what's not black and white but grey all over? https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000qlsk

And the following books:

Walker, R. (2001) Black, white and Jewish: Autobiography of a shifting self. New York.Riverhead.

Williams, J. (2008) Michael X: A Life in Black and White: London: Century